DANIEL LAWSON

Bioreactor

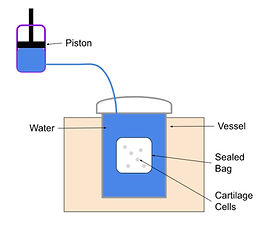

Goal: To build a bioreactor that can apply a cyclic hydrostatic pressure of 10 Mpa (1500 psi) to cartilage organoids at a rate of 1 Hz, and maintain a temperature of 37C.

Background

This bioreactor was my capstone project at Northeastern University. My group's advisor was Dr. Sandra Shefelbine, a bioengineering professor at NEU. She works extensively with cartilage organoids and identified the need for this bioreactor.

When growing cartilage organoids in vitro, conditions are mechanically dissimilar to those experienced

during in vivo growth. This causes matured cells to exhibit far worse mechanical properties than natural

tissue. The cells grown in the lab would be placed in the bioreactor for four hours a day to help them grow and become more similar to natural cells. The 10 Mpa at 1 Hz rate was chosen to replicate the forces that an average human knee feels when walking. After two weeks of four hours a day, the cells would reach full maturity and be studied for research on cartilage deseases and transplantaion.

Research

Applying pressure to grow cells is quite common, but we could not find others that did it cyclically as we wanted. Off-the-shelf bioreactors utilize high-pressure fluids to create hydrostatic pressure (HP) which are unable to create it quickly enough to hit our 1 Hz goal. Our plan was to utilize a hydraulic force machine that can quickly apply and release high forces to create this cyclic pressure.

Existing Bioreactor with Gas Inlet

Design Iterations

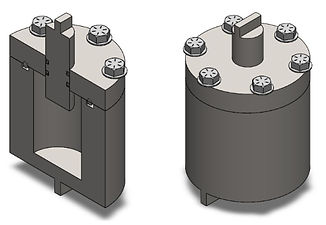

The first design utilized two vessels: one to create pressure and one to house the cells. This design was ultimately scrapped because it required the design and manufacturing of two vessels rather than just one. Additionally, the hose connecting the two vessels would require welded fittings. High-pressure welds require specialized certification, which our NEU machinists did not have.

After calculating that the displacement was only a couple of millimeters, we switched to a single-body design. The biggest problem with this design was the complex opening hinge.

As calculations for lid and body thicknesses concluded, we were able to move from a 2D drawing to a real 3D SolidWorks model. To circumvent the welding difficulties, the vessel would be made from a single piece of steel stock. Note here that the hinge was replaced with simple bolts: less user-friendly but more reliable and simple. The fins atop the plunger and at the bottom of the body were added to fit in the grips of the force machine.

Design 1

Design 2

Design 3

Final Design

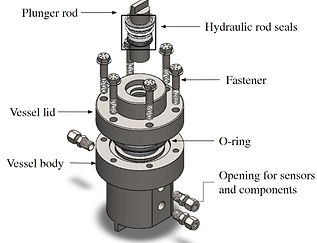

The significant changes made in Design 4, shown in Figure 21, are a result of updated calculations made for the bolts on the lid, the vessel size and wall thickness, the lid thickness, added NPT holes, and the use of rod seals.

Final Design

Body: Four 1/4NPT holes were added to allow for a pressure gauge, release valve, thermistor, and fill hole. The calculations for body thickness conformed with ASME standards for pressure vessels. The faces with the holes were milled to allow for proper tapping. The FEA below shows the pressure concentrations with the added holes.

Pressure FEA

Lid: The lid thickness was increased to create more surface area for the seals. The calculations for lid thickness conformed with ASME standards as well.

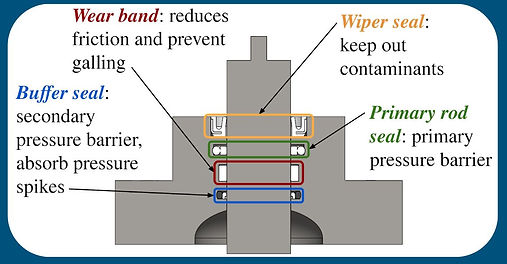

Seals: After conversations with seal experts and countless hours of seal research, we decided to mimic a setup commonly used in hydraulic pistons. However, we had to select materials that would not need lubrication unlike those in hydraulic systems. All seals are put into internal grooves on the static lid, rather than in the dynamic piston.

Seal Configuration

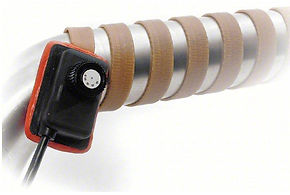

Temperature Control: To heat the bioreactor, the vessel was wrapped in heating tape. A thermistor was placed in one of the NPT holes and both were connected to a control circuit with an Arduino. A relay was used to switch the heater on and off. To quicken the heating process of the thick steel, the bioreactor would be filled with hot water to start.

Heat Tape

Thermistor

Safety: To monitor the pressure, a digital pressure gauge was added. In case too much force was applied, a pressure release valve was added to vent excess pressure safely.

Execution and Testing

Xomety, a third-party machinist, manufactured the vessel for us. Almost all materials were sourced from McMaster-Carr. It was learned two weeks prior to Capstone Day that the Instron force machine, meant to be used for the full cyclic loading tests, broke. Since there were no other machines on campus that could provide this cyclic force, we were unable to test it at the four-hour run time, however, we were able to test momentary pressure on a hand press.

.png)

.png)

Small NTP Leak

Hitting Target Pressure

Homemade Instron

In the end, we were able to hit target pressure with only a small leak through one of the NPT holes. To us, this was a monumental success because none of the parts we designed failed. We are confident that with some new Teflon tape and retorquing the plug would prevent a leak. However, given the timeframe of this project, we were unable to try again. We were unable to test the heating system as it arrived the night before Capstone Day, but that should be simple in relation to the rest of the components.

Future Work and Conclusion

While the vessel succeeded at holding pressure, the temperature system must still be tested. This is a relatively straightforward task that involves completing the control circuit. One of the group members will continue working with Dr. Shefelbine to close the loose ends next semester. Additionally, the bioreactor must be tested at its four-hour run time on a hydraulic force machine. Unfortunately, there is no estimate of when the NEU machine will be fixed.

.png)

The Team on Capstone Day

In the end, we and our advisor are very proud and happy with the work we did. To our understanding, this is the only pressure vessel that translates uniaxial force into hydrostatic pressure in this way. Furthermore, no members of the group had worked with high-pressure systems prior and we all learned everything on the way. It is very encouraging to know that I can learn an entirely new and intimidating topic, like high pressure, and use it to engineer a functional and helpful device.